[ad_1]

In the rolling hills near Penobsquis, almost every tree has been cut down for as far as the eye can see.

Greying piles of stumps and woodchips occasionally clot the bare landscape, and a single strip of trees has been left to shade the small streams at the base of the hills.

The former forest in southern New Brunswick, now a series of clearcuts, is known to local conservationists as the Red Dragon.

And according to some scientists and conservationists, the Red Dragon, along with countless other tree-shorn areas in the province, contributed to the record flooding along the St. John River this spring.

Rapid warming

Clearcuts on the hills near Penobsquis in southern New Brunswick have left much of the area bare and earned it the name ‘Red Dragon’ among local conservationists. (Shane Fowler/CBC)

Floodwaters ravaged homes, cottages and infrastructure and threw questions about how and why into conversations all along the southern reaches of the river.

Meteorologists pointed to the rapid shift from winter temperatures to summer-like conditions as the main culprit.

But many whose properties were pulverized asked if clear-cutting boosted the magnitude of the flood.

In his blog, Green Party Leader David Coon pointed to research by André Plamadon for the Quebec Department of Natural Resources, who found that when more than half a watershed has seen clear-cutting in the previous 35 years, “the spring freshet may be severe enough to cause physical changes to local watercourses.”

Recent research

The spring flood caused catastrophic damage to homes, cottages and infrastructure. Among the hardest hit were communities along Grand Lake, where some homes and cottages were destroyed. (Shane Fowler/CBC)

Kim Green, a fluvial geologist in British Columbia, studies streams and watersheds, and the links between forest removal and flooding.

She has spent decades researching how snow and water behave in forested areas and after clearcuts, and says that mature, undisturbed forests mitigate flooding.

“You take the trees away and the first thing that happens is you no longer have the canopy of the trees that was originally intercepting snow,” said Green, who got her doctorate from the University of British Columbia and teaches at Selkirk College.

“The forest canopy is actually removing snow from the equation.”

Kim Green, a fluvial geologist in British Columbia, has spent years studying how the removal of forests can lead to a greater magnitude and frequency of flooding. (Submitted: Kim Green)

Green believes reduced absorption is another major impact of forest removal. When snow melts slowly, trees drink more of the meltwater. A lot more.

“Through the spring period, in particular, trees are consuming a lot of water,” she said in an interview from her home in Nelson, B.C. “Your average tree is consuming about 150 cubic metres of water every year.”

“So about 16 trees or so are consuming an Olympic swimming pool-sized amount of water.”

The process is called evapotranspiration, she said.

“The roots are just sucking that water out of the soil.”

More sun on the snow

Canadian researchers say the forest canopy can keep as much as 60 per cent of snow from ever reaching the ground, thus reducing the potential flood threat come spring. (CBC)

Perhaps the most significant impact is the one obvious even to laypeople. Without a canopy to shade the snow on the ground, it melts a whole lot faster when the temperature starts climbing.

“You have a lot more solar radiation getting directly onto the snowpack and that is melting it much faster,” said Green from her home in Nelson, B.C.

“And it’s also melting it, generally, earlier. So earlier, faster.”

This combination, she said, gets the snowmelt into streams and river systems fast and effectively.

Snow, shade and soil

John Pomeroy, the Canada Research Chair in water resources and climate change, says research in Saskatchewan has found more runoff flowing into streams from clearcuts than from areas with a forest canopy. (Erin Collins/CBC)

John Pomeroy’s research has shown the same thing.

“We know that in northern Saskatchewan you get about seven times more runoff to stream flow from clear-cut areas in the spring than you do from the surrounding forest canopies,” said Pomeroy, the Canada Research Chair in water resources and climate change at the University of Saskatchewan.

“And those are probably rather extreme examples, but from that we can suggest that it’s still rather substantial in New Brunswick.”

Operations during wood harvesting can compact soils to the point where they hold a small fraction of the water they did before, Pomeroy says. (CBC)

About one-tenth the sunlight reaches the ground under a forest canopy than in a cleared area, said Pomeroy, who is also director of the Centre for Hydrology in Saskatchewan.

“So there’s a lot of heat energy from that solar radiation that isn’t there to melt the snow.”

Scientists argue clearcuts like this one in Tracy, south of Fredericton, lead to faster-melting snow because of the lost shade provided by tree canopy. The melt can be three to seven times as fast, resulting in floods. (Shane Fowler/CBC)

Compacting the ground during the harvesting of trees can also add to flooding woes. Wherever heavy machinery is used the soil becomes more compacted and less spongy and holds less water.

“And it’s the amount of water the soils hold under a forest that is really important in holding back floodwaters,” Pomeroy said.

The Red Dragon

After the trees on the hills near Penobsquis were harvested, the area showed up as a massive red blotch on Frank Johnston’s satellite maps.

Johnston is retired but serves on the board of the New Brunswick Conservation Council and monitors satellite imagery of New Brunswick’s reduced forest canopy from Global Forest Watch.

We’ve lost approximately 20 percent of our forest cover since the year 2000.– Frank Johnston

From space, he said, the clearcuts near Penobsquis resemble the red dragon on the national flag of Wales. Hence the “Red Dragon.”

“It looks a bit like a desert,” said Johnston, who has degrees in biological sciences from the University of New Brunswick, McMaster University and the University of Calgary.

Much of the Red Dragon clearcut in the St. John River watershed remains bare a few years after the trees disappeared. (Shane Fowler/CBC)

The Global Forest Watch web program was developed with the University of Maryland, NASA and Google, among others, to monitor the loss of forest across the planet.

An algorithm shows areas of New Brunswick that have changed from “green” to “brown,” signifying a loss of forest canopy.

The province is rapidly turning “brown,” according to Johnston’s data.

“New Brunswick’s forests are in some danger,” he said. “We’ve lost approximately 20 percent of our forest cover since the year 2000,” he said.

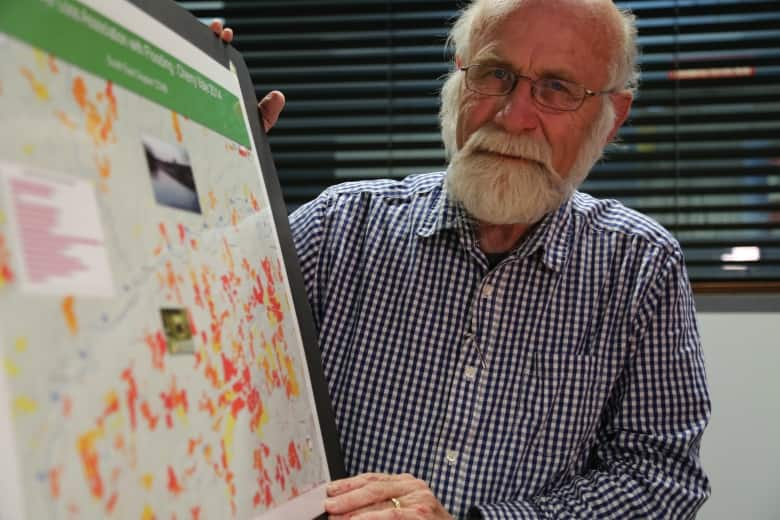

Frank Johnston, a member of the New Brunswick Conservation Council board, is convinced the province suffered severe floods this spring in part because of clearcuts. (Shane Fowler/CBC)

“It’s about twice what neighbouring jurisdictions, Maine, Nova Scotia, Quebec, harvest in their forests.”

Johnston also sees the deforestation from the air, with his own eyes, in a chartered plane equipped with GPS cameras.

Excluding “protected” areas, it is virtually impossible to find a part of the province that has not been cut down, he said.

“New Brunswick has virtually no intact forests.”

Johnston is convinced clear-cutting played a role in the spring flooding in the St. John River watershed, and the Red Dragon is just one of many areas in the watershed that contributed.

But not everyone agrees.

Industry research

J.D. Irving Ltd. says it has financed research into watershed management and the effect of “forest management” on the flow and temperature of water and on silt levels.

“There is no indication that our forest management activity is having a significant impact at the landscape scale on any of these variables,” said Mary Keith, the vice-president of communications at JDI, the only major forest company in the province to respond when CBC News asked for interviews.

Roughly 25% of the harvested area is planted and the remainder of the forest quickly regenerates naturally to softwood, mixed wood or hardwood conditions.– Mary Keith, J. D. Irving Ltd.

Keith also said that in this region, the company defers to “local scientists who are familiar with our geography.”

She pointed to biologist Allen Curry, a UNB professor and one of the science directors of the Canadian Rivers Institute, a group focused on making rivers healthy.

“In any landscape, if you remove the vegetation from that landscape you’re going to change how the water moves across that landscape and what it’s going to do,” said Curry, who for decades has taught biology, forestry and environmental management.

He agreed the science is clear about the impact of forest removal on melting snow and runoff.

Connection dismissed

Allan Curry, a professor at the University of New Brunswick, doubts clear-cutting is a factor in flooding because it’s not done on a scale that would make a difference. (Shane Fowler/CBC)

But he doesn’t believe clear-cutting is connected to the spring flood.

“We simply don’t have that scale of tree-cleared land in the St. John River Valley to be taken seriously as a contributing factor,” he said.

Clearcuts would be just a small factor in the higher river, he said.

“Probably not even significant — because that is not a major player in our watershed here in the St. John system.”

The New Brunswick government and forestry company J.D. Irving Ltd. say that areas where forests are cut regenerate ‘quickly.’ But some scientists say cuts like this one near Little Lake, southwest of Fredericton, will take nearly a century to grow back. (Shane Fowler/CBC)

Curry also noted that forestry companies often plant new trees on the land they clear.

“Typically, when you first clear the land, it creates an increase in water flow across the land and into the river,” he said. “It changes how the water is accumulated and how the groundwater is as well.

“But in a forestry situation, after about five years, you start to get the vegetation coming back, and the hydrology starts to stabilize a bit.”

JDI said it plants more trees than it cuts.

“Roughly 25% of the harvested area is planted and the remainder of the forest quickly regenerates naturally to softwood, mixed wood or hardwood conditions,” Keith said in her email.

New Brunswick clearcuts, such as this one outside Saint John, are often replanted with select species of trees after harvesting, but those can take decades to grow to a point where they can shade snow. Some scientists argue the young trees can actually accelerate the melt. (Shane Fowler/CBC)

But what does “quickly” really mean?

Kim Green and John Pomeroy both said it takes decades to bring a forest back to the point where it can effectively retain large amounts of water.

“It’s normal practice in Canada to replant forests,” Pomeroy said. “So after 10 or 20 years you get a forest of smaller trees. In many cases, in 30 to 40 years, they are starting to look pretty big.

“But they don’t always behave like a mature forest for up to 100 years.”

J.D. Irving Inc. says it replants roughly 25 per cent of the areas where it cuts trees. Scientist Kim Green says the young saplings can act like ‘heat sinks’ and actually reflect sunlight into the snowpack, leading to an even faster melt. (Shane Fowler/CBC)

New growth

Those big trees do the best job of holding water when storms and floods hit, he said.

What’s more, Green said, until the planted trees are big enough to provide shade, they can make things worse when the temperature rises.

“What happens is the little green stems are absorbing the heat, the incoming heat,” she said. “Then they are reflecting it into the surrounding snowpack.”

The result is an even faster melt than happens with the clearcut.

“It can take 50 years, 60 years, 70 years to really start seeing any recovery in a regenerating stand,” Green said.

The New Brunswick government says research in other parts of Canada into the link between deforestation and flooding does not apply to the snow, forest or river systems of this province. (Shane Fowler/CBC)

Like JDI and Curry, the provincial government also maintains that deforestation is not a flooding factor in New Brunswick.

The Department of Energy and Resources Development “tracks the area harvested each year on Crown lands, and harvests are kept within long-term sustainable levels,” said spokesperson Jean Bertin.

“Less than two per cent of the forest is harvested each year, and clear-cutting is used on only a portion of that land.”

Future forests

Echoing JDI, Bertin said research elsewhere on forest removal and flooding should not be applied to New Brunswick.

“It’s acknowledged in watershed research that lessons learned from research done in one watershed or jurisdiction,” said Bertin, who is not a scientist.

“It is challenging to ‘transfer’ to other watershed or jurisdictions because of the complex variables involved.”

Many clearcuts in New Brunswick look like this one outside Sussex, according to Frank Johnston, who monitors the changing picture of forests by plane and satellite. (Shane Fowler/CBC)

Green agreed there are some obviously different variables in different regions but said her research in British Columbia applies to New Brunswick.

“Snow melts the same way regardless of where you are,” she said. “And forests tend to have the same effect on that snowmelt.”

As the frequency and magnitude of floods increase in some areas, Green said, she is seeing a shift in government forestry policy, at least in B.C.

“Things definitely need to be changing,” she said. “There needs to be an awareness about the sensitivity of streams to logging that’s currently not out there within our provincial regulation frameworks.”

[ad_2]