Among the many winter survival strategies in the animal world, hibernation is one of the most common. With limited food and energy sources during winters – especially in areas close to or within polar regions – many animals hibernate to survive the cold, dark winters. Though much is known behaviorally on animal hibernation, it is difficult to study in fossils.

According to new research, this type of adaptation has a long history. In a paper published Aug. 27 in the journal Communications Biology, scientists at Harvard University and the University of Washington report evidence of a hibernation-like state in an animal that lived in Antarctica during the Early Triassic, some 250 million years ago.

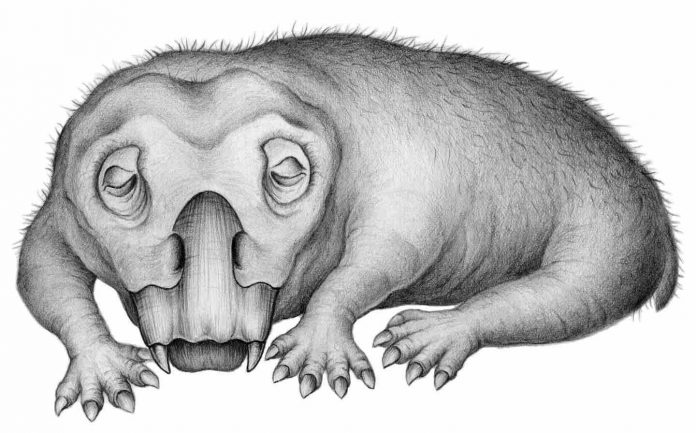

The creature, a member of the genus Lystrosaurus, was a distant relative of mammals. Lystrosaurus were common during the Permian and Triassic periods and are characterized by their turtle-like beaks and ever-growing tusks. During Lystrosaurus’ time, Antarctica lay largely within the Antarctic Circle and experienced extended periods without sunlight each winter.

“Animals that live at or near the poles have always had to cope with the more extreme environments present there,” said lead author Megan Whitney, a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard University in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, who conducted this study as a UW doctoral student in biology. “These preliminary findings indicate that entering into a hibernation-like state is not a relatively new type of adaptation. It is an ancient one.”

The Lystrosaurus fossils are the oldest evidence of a hibernation-like state in a vertebrate animal and indicate that torpor — a general term for hibernation and similar states in which animals temporarily lower their metabolic rate to get through a tough season — arose in vertebrates even before mammals and dinosaurs evolved.

Lystrosaurus arose before Earth’s largest mass extinction at the end of the Permian Period – which wiped out 70% of vertebrate species on land – and somehow survived. It went on to live another 5 million years into the Triassic Period and spread across swathes of Earth’s then-single continent, Pangea, which included what is now Antarctica. “The fact that Lystrosaurus survived the end-Permian mass extinction and had such a wide range in the early Triassic has made them a very well-studied group of animals for understanding survival and adaptation,” said co-author Christian Sidor, a UW professor of biology and curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Burke Museum.

Today, paleontologists find Lystrosaurus fossils in India, China, Russia, parts of Africa and Antarctica. The creatures grew to be 6 to 8 feet long, had no teeth, but bore a pair of tusks in the upper jaw. The tusks made Whitney and Sidor’s study possible because, like elephants, Lystrosaurus tusks grew continuously throughout their lives. Taking cross-sections of the fossilized tusks revealed information about Lystrosaurus metabolism, growth and stress or strain. Whitney and Sidor compared cross-sections of tusks from six Antarctic Lystrosaurus to cross-sections of four Lystrosaurus from South Africa. During the Triassic, the collection sites in Antarctica were roughly 72 degrees south latitude — well within the Antarctic Circle. The collection sites in South Africa were more than 550 miles north, far outside the Antarctic Circle.

The tusks from the two regions showed similar growth patterns, with layers of dentine deposited in concentric circles like tree rings. The Antarctic fossils, however, held an additional feature that was rare or absent in tusks farther north: closely-spaced, thick rings, which likely indicate periods of less deposition due to prolonged stress, according to the researchers. “The closest analog we can find to the ‘stress marks’ that we observed in Antarctic Lystrosaurus tusks are stress marks in teeth associated with hibernation in certain modern animals,” said Whitney.

The researchers cannot definitively conclude that Lystrosaurus underwent true hibernation. The stress could have been caused by another hibernation-like form of torpor, such as a more short-term reduction in metabolism. Lystrosaurus in Antarctica likely needed some form of hibernation-like adaptation to cope with life near the South Pole, said Whitney. Though Earth was much warmer during the Triassic than today — and parts of Antarctica may have been forested — plants and animals below the Antarctic Circle would still experience extreme annual variations in the amount of daylight, with the sun absent for long periods in winter.

Many other ancient vertebrates at high latitudes may also have used torpor, including hibernation, to cope with the strains of winter, Whitney said. But many famous extinct animals, including the dinosaurs that evolved and spread after Lystrosaurus died out, don’t have teeth that grow continuously.

“To see the specific signs of stress and strain brought on by hibernation, you need to look at something that can fossilize and was growing continuously during the animal’s life,” said Sidor. “Many animals don’t have that, but luckily Lystrosaurus did.” If analysis of additional Antarctic and South African Lystrosaurus fossils confirms this discovery, it may also settle another debate about these ancient, hearty animals. “Cold-blooded animals often shut down their metabolism entirely during a tough season, but many endothermic or ‘warm-blooded’ animals that hibernate frequently reactivate their metabolism during the hibernation period,” said Whitney. “What we observed in the Antarctic Lystrosaurus tusks fits a pattern of small metabolic ‘reactivation events’ during a period of stress, which is most similar to what we see in warm-blooded hibernators today.” If so, this distant cousin of mammals is a reminder that many features of life today may have been around for hundreds of millions of years before humans evolved to observe them.