The hormone, ghrelin, may help protect the elderly population from muscle loss, according to a study being presented at e-ECE 2020. The study found that administering a particular form of ghrelin to older mice helped to restore muscle mass and strength. As muscle-related diseases are a serious health concern in the elderly population, these findings suggest a potential new treatment strategy for muscle loss to enable the aging population to remain fit and healthy.

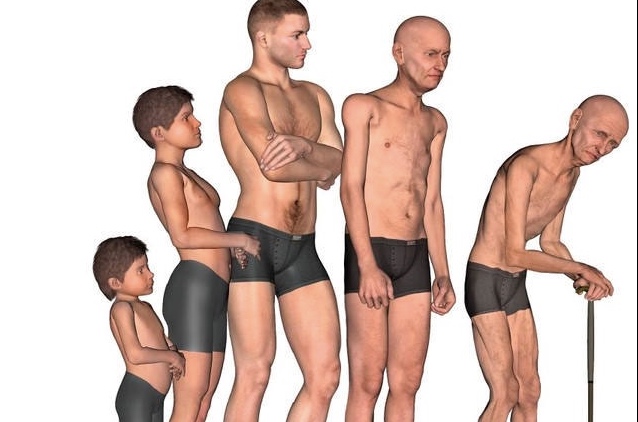

Age-related skeletal muscle mass loss, in absence of any underlying disease, is defined as sarcopenia, which leads to deterioration of elderly people’s quality of life. It causes a decline in muscle mass and functionality, often resulting in poor balance, higher risk of falls or fractures, immobilisation and loss of independence.

Ghrelin is a hormone involved in metabolic regulation and energy balance through activation of appetite, but also plays an important role in protecting against muscle wasting. Both acylated (AG) and unacylated (UnAG) forms are present in the body, but UnAG does not bind to the AG receptor (GHSR-1a), so does not increase appetite. A growing body of evidence indicates that UnAG is acting at an unidentified receptor, which also mediates some common AG and UnAG biological activities, including a strikingly protective effect against muscle wasting. Ghrelin levels decline as we age and may be involved in the development of sarcopenia, but the role of AG versus UnAG in this process has not been investigated previously.

Dr Emanuela Agosti, and her team at the University of Piemonte Orientale in Italy, investigated how unAG affected age-related decline of muscle mass and function, by either deleting the ghrelin gene in mice, or overexpressing unAG. Muscle function as they aged was assessed through a wire hanging test, during which “falling” and “reaching” scores were recorded, to assess whole body strength and endurance. Both the deletion of the ghrelin gene and the lifelong overexpression of UnAG reduced age-associated decline in muscle mass and function. Despite both groups of animals displaying similar aging tendencies in body weight and muscle mass, the mice overexpressing UnAG maintained better muscle structure, performance and metabolism, more typical of muscle in younger mice.

“Understanding the causes and effects of sarcopenia will improve our ability to prevent, detect, and hopefully manage this disease. These findings provide novel understanding and point to UnAG, or analogues, as a possible therapeutic target for future treatment,” Dr Agosti comments.

The study indicates that UnAG, or possibly drugs that mimic it, can preserve muscle function and reduce the risk of age-related sarcopenia, without causing weight gain and obesity.

“Due to the worldwide increase in the elderly population, sarcopenia has an important social impact greatly affecting both aged people’s quality of life and government health care costs. Therefore, therapeutic strategies aimed at preventing and/or reducing sarcopenia are of pivotal importance.” Dr Agosti adds.

Dr Agosti and her colleagues now plan to identify the receptor mediating UnAG biological activities. This will help better define the molecular pathways involved in AG/UnAG actions and to design treatments that may reduce loss of muscle mass in sarcopenia and other similar conditions.