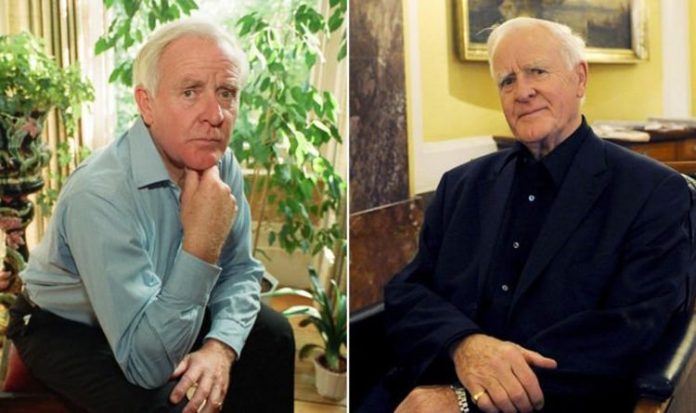

John le Carré on his novel ‘Agent Running in the Field’ in 2019

The spy writer, whose depiction of the Cold War remains vivid 60 years after his anti-hero George Smiley first made his appearance, is worthy of a spy novel himself. Shadowy, distant, but brilliant, le Carré sometimes told the truth and often he didn’t. But then he’d learnt to lie from childhood, claiming his father was a spy when in fact he was nothing more than an upper-class con man. Apprenticed early to the art of fabletelling, le Carré – born David John Moore Cornwell – was destined to write, but he can have had no idea his books would become world best-sellers, and that he would spark a writing genre as strong and thrilling today as when he invented it.

Readers in their tens of millions were sucked into the world he created, peopled with dark, seedy characters whose lives were worthless, whose prospects of salvation zero. Yet his books from Call For the Dead to Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and The Spy Who Came in From the Cold maintained a high moral tone – as if he wanted to protect readers from the evils of murder and betrayal.

He also created a spying jargon so convincing former colleagues adopted it as their own: surveillance officers were ‘lamplighters’; ‘pavement artists’ would follow targets, and the ‘scalphunters’ were a section specialising in burglary, blackmail and murder.

The whole glorious shebang of MI6 was known as the Circus.

His death at the age of 89 prompted fellow writers to pay tribute to his unequalled work. Inspector Rebus author Ian Rankin praised him for taking spy fiction “into the realms of literature” while Fatherland author Robert Harris said: “He was a writer of immense quality who transcended his genre.” TV viewers will remember either Alec Guinness as the world-weary Smiley in the BBC’s 1979 adaptation of Tinker, Tailor… or Gary Oldman from the equally spellbinding 2011 film.

Le Carré had a troubled relationship with his father (Image: Mirrorpix)

The standout screen adaptations include Richard Burton’s chilling portrayal of anti-hero Alec Leamas in the 1965 The Spy Who Came In From The Cold, and, more recently, The Night Manager mini-series in 2016 starring Tom Hiddleston and Elizabeth Debicki.

But it was the books, not their adaptations, le Carré will be remembered for.

He was the writer’s writer – for not only did he invent a genre but he wrote it in impeccable prose, so even readers with no interest in espionage would lap up his pages simply because they were so delicious to read. But who was John le Carré, and why was he so good?

Born in Poole, Dorset, in 1931 to Ronnie and Olive Cornwell, his childhood was a misery. Olive left home when he was five, and he was then alone with his shady, double-dealing father whom he both loved and hated.

“He grew up in a house full of mysteries and disappearances,” his biographer Adam Sisman recalled.

“Brought up in a world of deceit, you had to fabricate to survive. Having such a domineering father meant he had to develop a secret life – he started going through his father’s coat pockets to find out what was going on.

“His father didn’t admit until he [le Carré] was an adult that he’d served a jail term, and his mother left late at night without saying goodbye,” said Sisman. As a boy, le Carré told school friends his father had been a spy.

Sisman explained: “He was of a generation, during the war, that what your dad did was terribly crucial. Ronnie was that most despised person, a war profiteer, rather than away at the front fighting in the army.”

“He was sent to Sherborne, the Dorset public school, but ran away when he was 17. And here the truth and the fiction of his life start to collide – he claimed he’d been recruited by MI5 to spy on student groups in Bern, Switzerland.

Later on, as an Oxford undergraduate, he spied on left-wing fellow students.

Well, he may have – and then again, perhaps not: “Part of his problem was that he told different stories [about his life] at different times and no longer knew what was true,” says Sisman, who spent hours talking with the author.

Le Carre, pictured in 1965, died of pneumonia (Image: Getty)

What is certainly true is that he did his National Service in the Army Intelligence Corps where he learnt the tradecraft of running low-grade agents in the communist Eastern Bloc.

He then spent two years teaching at Eton – “Its snobbishness appalled him, and he wrote cruel portraits of two of its beaks [masters] in A Murder of Quality,” recalled the historian Kenneth Rose – before joining the Foreign Office.

There, he finally entered the twilight world of espionage, working at the British Embassy in Bonn as a Second Secretary, the usual secret agent’s cover.

Part of his job was to interrogate Czech defectors. As he worked in the intelligence records department he started to scribble down ideas for spy stories, and his first novel, Call For the Dead, was published in 1961 while he still toiled undercover. When his third novel, The Spy Who Came In From The Cold, was turned into a film starring Richard Burton, he took up writing fulltime, producing 25 novels over the next six decades as well as short stories, screenplays and non-fiction.

Though undoubtedly Britain’s most successful literary novelist, he refused all thoughts of accepting an honour – “There will never be a Sir David Cornwell,” he declared.

Gary Oldman took the role first played by Alec Guinness (Image: Reuters)

For although he gave the appearance of being patrician and for all the world a product of the upper-classes, le Carré remained an outsider, refusing for years to allow interviews and discouraging journalists from uncovering his espionage past or messy personal life. But you didn’t need to be a psychiatrist to trace le Carré’s infidelity to his miserable childhood.

Indeed, in his books all roads lead back to those early years – most revealingly portrayed in A Perfect Spy (1986), possibly his finest book.

In it, Magnus Pym is a British spy who betrays his country, and as the tale unfolds we learn of his charismatic con man father Rick Pym, a photofit of Ronnie Cornwell, who at one time was an associate of the notorious Kray twins who led organised crime in London for a decade.

Le Carré’s father made and lost several fortunes through elaborate confidence schemes – his period in jail was for insurance fraud. Another biographer, Lynndianne Beene, described Ronnie as “an epic con man of little education, immense charm, extravagant tastes, but no social values”.

The author himself confessed: “Although I’ve never been to a shrink, writing A Perfect Spy is probably what a very wise shrink would have advised me to do anyway.”

Sir Alec Guinness as ‘George Smiley’ (Image: BBC)

In his autobiography, The Pigeon Tunnel, he claimed to have been dispatched to postwar Paris by Ronnie aged 16 where he narrowly escaped seduction by a diplomat and his wife. It was 1947 and the teenager had been sent by his roguish father to collect a £500 debt from the Panamanian ambassador to France.

Having been plied with alcohol, the “most desirable” woman he had ever seen “kicked off a shoe and caressed my leg with a stockinged toe” before her husband “decided we were ready for bed”. Making his excuses, le Carré left alone and slept on a park bench.

The “sensuous, unfulfilled” night would inspire works such as The Tailor Of Panama. Years later, he failed to find the house and restaurant and later still while visiting Panama on a research trip, he made enquiries about his erstwhile host but nobody could recall a count from Panama. In his 2016 memoir, he wrote: “Nobody had heard of the fellow. A count? From Panama? It seemed most improbable. Maybe I had dreamed the whole thing?”

Le Carré, who reportedly amassed a £75million fortune, married twice – first in 1954 to Alison Sharp and then to Valerie Eustace. There were three sons from the first marriage. His son from the second writes novels under the name Nick Harkaway.

For the past 40 years le Carré lived between north London and St Buryan in Cornwall, eventually buying himself a mile of clifftop on which he could walk around, voicing his latest characters and plots.

His final published work, Agent Running In The Field, came out last year – but he never ceased working up to his final illness, and it’s not unreasonable to hope for one final book under his name before too long.

Let’s hope it’s a Smiley!