Fleetwood Mac: Lindsey Buckingham joins tour in 1977

I AM an old hippy. Most people could never imagine me doing anything more creative than frying onions on a hotdog stall outside Wembley Stadium. But during the golden era of the British music industry, I was the man with the Midas Touch. As Head of A&R (Artists and Repertoire) at EMI Records, I worked with many of the world’s best-selling stars, including the likes of Paul McCartney, Queen, Pink Floyd and Kate Bush. I discovered, signed and made superstars of the Sex Pistols, who I found in the dingy old 100 Club on Oxford Street, London; Duran Duran, who came my way fully-fledged if a little rough around the edges via a nightclub in Birmingham called Holy City Zoo; and the Pet Shop Boys, Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe, who were introduced by a record-sleeve designer.

I was never your typical music business executive. I had been a professional musician, for a start.

I was the first bass player with Fleetwood Mac, a band that had evolved out of the Peter Bs, performing alongside my old mates Peter Green – the gifted but doomed creator of Albatross and Black Magic Woman – and Mick Fleetwood, lanky drummer extraordinaire and backbone of the band to this day. But I left the Mac before they hit the big time because I wanted a quiet life.

I’d played with Ray Davies, Rod Stewart, Jeff Beck, Cat Stevens and Jimi Hendrix, tasting embryonic stardom with Brian Auger and the Trinity when I strummed alongside the delectable Julie Driscoll on our chart-storming cover of Bub Dylan’s This Wheel’s on Fire. But rock stardom didn’t do it for me. I wanted more.

Born in 1945 and growing up in Highgate, north London, my background was dysfunctional and abusive. My sister Philly and I were deserted by our parents. I was abandoned to boarding school, where I was interfered with. Not that I ever told anyone. We didn’t, in those days.

Music, as it is for so many, was my escape and my salvation. I would go so far as to say that it saved my life. I discovered it as a schoolboy, learned to play the guitar and never looked back.

I progressed to west London’s Byam Shaw School of Art in 1963, where I didn’t try very hard because I was by then in constant demand as a musician.

How bad can it have been: posh kid, expensive education, awash with dosh, musical success and pending stardom? I had a life that millions of people craved. I’d have to be mad to give it all up.

But I did, because I wasn’t a pop star. I was a bass player. The limelight never felt right.

Wild keyboardist Brian Auger used to tell me I “looked bemused” by our sudden breakthrough that brought appearances on Top of the Pops and huge coverage on the radio and newspapers. I would stand around at those pretentious pop parties feeling like an outsider.

Was all this really what I wanted to be doing with my life? I began to feel more like a pair of hands affixed to a bass guitar than a functioning human being. All that flying around the world and being dropped on a stage in front of baying crowds did nothing to reassure me otherwise.

I was starting to lose my mind. I remember doing a show in a circus tent somewhere, and looking out into the audience to see Salvador Dalí staring back at me. Did I? Or was I seeing things?

The tours, festivals and recording studio capers, the endless girls, booze and drugs, the naked women mud-wrestling backstage before Queen concerts, it was all huge fun at first.

I was easy on the eye, and I had my share of women. Even the infamous Cynthia Plaster Caster, the American groupie and artist who made her name creating casts of the private parts of rock stars, pursued me for a while.

In 1977, I went to the Rainbow Theatre in north London to see my old pal Mick Fleetwood and the band, which now featured John and Christine McVie, Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks.

Thanks to the gigantic, Grammy Award-winning success of their album Rumours, nothing for them would ever be the same again.

I remember Mick’s eyes glistening with mischief as he stood staring at me in his bouquet-stuffed dressing room.

“Dave!’ he cried expansively, throwing his leg-length arms as wide as the Thames. All this could have been yours!”

“You know me, Mick,” I smiled. “The one who got away.”

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t care. Fleetwood Mac were the biggest group in the world by then. They were buying mansions the way the rest of us buy books.

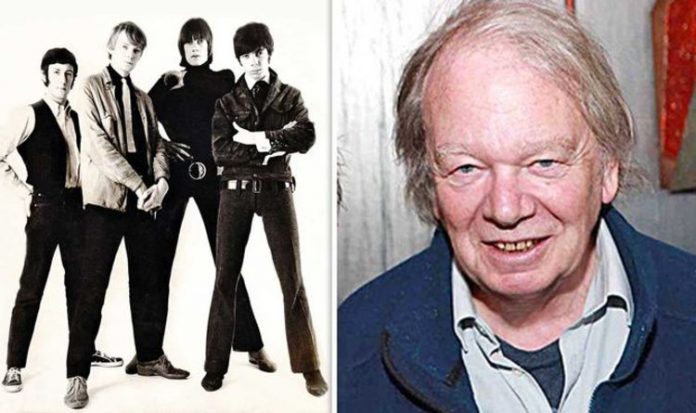

Fleetwood Mac forerunners the Peter B’s starring, second left, David Ambrose; David today (Image: David Ambrose / Little Wing Books)

I pictured them bathing in champagne, having mind-blowing passionate encounters with whoever took their fancy in Learjets and on the back seats of limousines.

Their tangled love lives made A-list movie stars look like losers.This was all so far removed from the quaint little plans Mick and I used to sit around making when we were teenagers that I burst out laughing.

Did I regret walking away? Not especially. I knew myself too well.

The stark truth was that I would never have survived what they had become. I would have gone for it, no holds barred.

I would have drunk too much, drugged too much, had sex too much and died too much. It looked easy from the outside. I knew to my cost that it was anything but. In their shoes, I would have been the ultimate rock’n’roll suicide.

Some are born to live their life in the limelight; to put up with the drag of touring and performing, having to create music to order from scratch in the studio when you’d been sick all night, being deprived of a private life, needing security just to go to the lavatory.

I clearly remember the sinking feeling when everyone wants a piece of you, but never knowing for certain that you’ve got a friend, or whether they love you for the money and the glory – and would no longer want to know you once your luck had changed. Because it always changes.

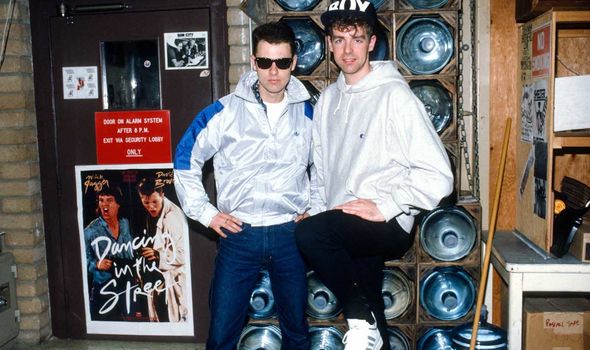

The Pet Shop Boys were discovered by David Ambrose (Image: Getty)

I reminded myself I was the lucky one. I might have been a has-been, living from wage packet to wage packet.

But I had my beautiful wife Angie and children Kate, Barney and Rory. My friends were genuine. I knew where I belonged.

So I became an A&R guy for EMI, and helped enable other musicians wreck their lives with sex, drugs and rock’n’roll the way I hadn’t wrecked mine.

There were more near-misses than there were celebrated signings. That’s show business. My remit was broad, from Paul McCartney’s Frog Chorus song We All Stand Together – as I told him, an absolutely abominable record – to Tom Robinson’s 2-4-6-8 Motorway and Glad to be Gay which were outstanding.

And I bagged us new wave power popsters the Vapors, who had been discovered by the Jam’s bass player Bruce Foxton and whose Turning Japanese has never gone away.

How did it feel to be a hit-maker? I was bemused. Now that my name was linked to the pop sensations of the moment, news leaked beyond the industry. Wannabe stars started following me about and showering me with unwanted attention.

One even took his trousers off in front of me. Did I look like that kind of record company executive?

It was during Duran Duran’s 1985 sabbatical from each other to work on splinter projects that my importance as an A&R man was rammed home to me.

I visited Nick Rhodes and Simon le Bon in Paris to check on their glorious folly Arcadia.

The band released just one album, So Red the Rose, which only made Number 30 in Britain and Number 23 in America. Singer Simon Le Bon later described it as “the most pretentious album I’ve ever made”. Which was saying something.

If I’d found them decadent during the good old days, they’d gone beyond reason now. They had taken, not a luxury suite each, but an entire hotel floor.

Grace Jones, a guest on the album alongside Sting, Herbie Hancock and David Gilmour, was a frequent visitor.

Mick Jagger rocked up one night, looking like a gilded sculpture. I’d seen him before, of course, but never at point-blank range. I could hardly believe my luck.

At last, as one of the most successful A&R men in the land, I was about to sit down in a sumptuous suite in one of the most glamorous cities on earth and commune with one of the world’s greatest rock legends.

I admit, I was anything but cool. I bounded over, elbowed my way into his conversation, and started to talk, 19 to the dozen.

“Oh, do f*** off,” said Jagger, I was thrilled. Until then, the only rock star ever to have told me to f*** off was Paul McCartney.

Duran Duran members playing a gig in California (Image: Getty)

It was signing outrageous new wave band Sigue Sigue Sputnik that did for me. Perhaps I was losing my touch, I thought, as I left EMI to become Managing Director of MCA UK, where sex kittens were my remit.: Kim Wilde and Wendy James of Transvision Vamp, specifically. But MCA was shut down by its American owners almost before we got going.

I moved on to London Records, signed the Happy Mondays. They had seen better days. I failed to sign East 17, and the Spice Girls, who went to Virgin.

I also failed to sign any of the nineties Brit-pop acts I pursued – including Suede, Blur and Oasis. Each band slipped noticeably through my fingers.

I’d had my day. We all get there, don’t we?

Today I am a 75-year-old ex-A&R man who failed to become a rock star. But I can still play guitar and I can still dream. It’s not nothing.

How to Be A Rock Star by David Ambrose with Lesley-Ann Jones With a foreword by Mick Fleetwood is published by Little Wing Books priced £20. Visit www.littlewingbooks.com for more information