Mother and daughter united in grief (Image: -)

ON THE eve of the pandemic, Anne Mayer Bird and her daughter Catherine were widowed within 41 days of one another. They were then locked down alone, their grief and isolation broken just once a week when Catherine, 59, would visit Anne, 87. She would wear a mask and they would remain at a distance – but it was a contact of a sort.

Each Sunday, during these cherished visits at Anne’s home in north London, they talked, about the emotional isolation of losing a loved one during a global pandemic and the practicalities of widowhood.

Anne’s second husband John Bird died just before Christmas last year, a week before their 40th wedding anniversary.

“Barely two months after John died I was living in a world he wouldn’t have recognised. I lost my husband, whom I adored, and five weeks later – minutes really – I was locked up in the pandemic. I’d never lived alone in my life,” says Anne.

Then, just six weeks after John’s death, the husband of her youngest daughter, Catherine, died of pneumonia after falling ill in early December.

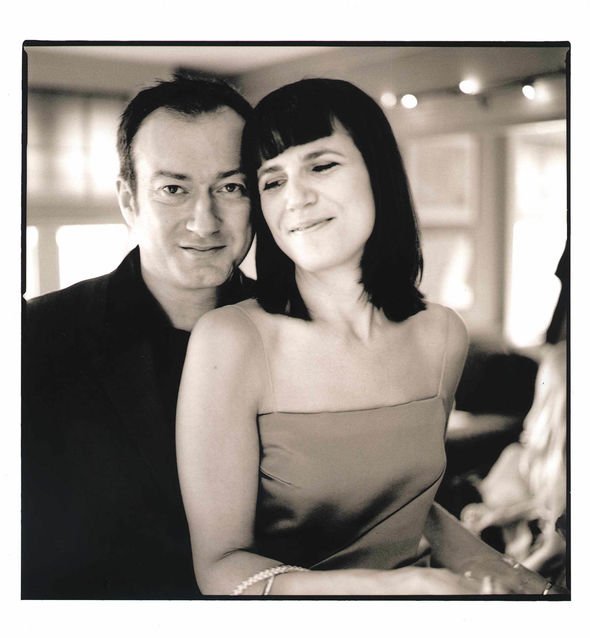

He was Andy Gill, the lead guitarist for Gang Of Four, the rock band he co-founded in 1976, who also produced albums for Red Hot Chili Peppers and The Stranglers.

The couple had been married for twenty years.

The Mayer family (Image: Mayer family)

“In losing the loves of our lives, my mother and I have found an ever closer relationship,” says Catherine, an author, award-winning journalist and co-founder of the Women’s Equality Party.

“Catherine puts on the double duvet that I can’t quite manage, and copes with my failures of technology.

“Being twin widows is not something we thought would happen, but we are up and running,” agrees Anne.

Together, mother and daughter are finding ways to navigate their loss and the challenges e , they face as twin widows, not least what they call “sadmin” and “dreadtape” – the painful administration that follows bereavement.

Catherine Mayer and husband Andy Gill (Image: )

They have also written an astonishing and deeply moving memoir, Good Grief, about how love can combat grief.

“Our book is a shaft of light in this very dark world,” says Anne.

And they have continued to seek answers to help explain their devastating losses.

In Catherine’s case this meant accepting the possibility that Andy contracted COVID-19 when his band toured China in November 2019.

The musician was admitted to St Thomas’ Hospital in London on January 1 struggling to breathe.

Had he been to China, the consultants asked. “He had, but I didn’t take this seriously to begin with because the timelines didn’t make sense,” says Catherine.

After being put into an induced coma, Andy died on February 1 at the age of 64.

This was the date that Catherine had agreed with his medical team for his life support to be turned off – to Fauré’s Requiem, which the couple often listened to at home to get to sleep.

“Andy’s organs were failing. He was judged too weak to tolerate a ECMO machine to oxygenate his blood outside of the body,” she explains.

It was only much later that stories began to emerge of COVID-19 infections in mainland Europe appearing before the established “first” UK cases.

This was followed by testimony from British infectious disease experts who said it was “completely possible” the virus was imported into the UK in December, if China had obscured the true date of the first infection – as now seems likely.

The first cases on British soil were identified on January 31, the day before Andy’s ventilator was turned off, when two Chinese nationals in York tested positive for COVID-19.

The UK’s earliest confirmed case of community transmission was a Nottingham woman who tested positive on February 21 and died on March 3, the day before Andy’s memorial.

“After Andy’s death, the Covid questions came quickly and were quite intrusive,” recalls Catherine of the public and press interest she faced at a time of immense grief.

“The hospital was already investigating, but we will never know conclusively. Yet looking at the pattern of the illness it makes sense.”

Anne Mayer marries John Bird (Image: -)

I ask her whether the suggestion that Andy died of COVID-19 has assisted her grief – mother and daughter suggest in the book that labelling a monster can make it less frightening.

There is a pause and, quietly, Catherine reveals her private anguish.

“The thing that torments me the most is that there are all these people like Michael Rosen, the poet and former Children’s Laureate, who is 10 years older than Andy, and he was on a ventilator for seven weeks…and I agreed to switch off Andy’s ventilator after five days. I try not to think of it. It’s traumatic.”

She pauses.

“There are more and more stories about people who survive for weeks and weeks…”

We are sharing our conference call with her mother Anne, 87, who is sharp as a tack and usually talkative.

“Darling, I didn’t know this,” she says gently.

“[Andy’s doctor] cannot rule out that there might have been a different outcome,” continues Catherine.

“Nobody knows. It’s certainly true that if he did have Covid and if he’d been treated later for it that they would have done very different things.”

The exchange lingers in the air for a moment, and then Catherine takes a breath and continues our interview, telling me how brilliant the hospital staff were and about the fundraising she has done.

But I can’t shake off her words for a few days and one can only imagine the strength she is having to muster to cope with the unanswerable questions she faces.

It is clear looking after her mother has helped in some way.

Anne has a gold-plated conviction that there is – and must be – life after death for those who remain.

“When you lose the person you love most in the world you think you can’t go on, but you can,” asserts Anne who has coped, in part, by writing letters to her much loved John.

“I wanted to tell him the extraordinary things that were going on. It didn’t make the grief go away, but it gave connection. I’m a [theatre] publicist by trade, I’m used to deadlines, and those letters gave shape to the day.”

The book came about after Catherine showed her mother’s remarkable letters to her publisher.

“Those letters were not written for publication, but John would be delighted that they are being published,”

Says Anne. “He always wanted me to write a book and I’ve realised his wish after he’s gone.”

For Catherine the book was initially more problematic.

“I really only wrote the book because I loved my mother’s letters to John so much. My publisher said, ‘what would really work is if you would write something that would wrap around them’,” she explains.

“I wanted the world to see the letters my mother had written. But it was also really painful, reliving some of the worst periods of my life. I’ve now written about Andy’s death, minute by minute, and read it aloud for an audio book.

“I didn’t have to go to other sources, but in order to do what I felt was a good and honest job I had to relive what I wrote. I hope that the honesty will help others.”

Catherine Mayer’s book (Image: -)

But she didn’t find writing it cathartic.

“People have this odd notion you can purge pain. They assume that grief and pain are analogous, but they really aren’t. Grief runs deeper and is more to do with connection. We are incredibly connected to the people we lose.”

She keeps some of Andy’s clothing in a Ziploc bag, hoping his scent will linger, and wears other items to absorb the memory of the man she loves.

“One of the things I’m trying to do is get his final album out. When the mix came through I was telling him how happy he would be with it. I had quite a long conversation with Andy, in fact.”

She says there is a notion grief has a timeline.

“And that you shouldn’t have any joy in that time and no laughter. My mother and I had to be self-reliant and reliant on each other, and we are doing more than surviving; we are living. Death is not the end of our lives, or of our lives with the men we love.”

• Good Grief: Embracing Life At A Time Of Death by Catherine Mayer and Anne Mayer Bird (HarperCollins, £16.99). For free UK delivery call Express Bookshop on 01872 562310 or order via expressbookshop.co.uk